In the past many people regarded sources of clean water as sacred, whether those sources were rivers, lakes, springs or wells. In Penwortham there were a number of wells associated with the area around Castle Hill. One of these wells, known in modern times as St Mary’s Well, has been obliterated by modern transport developments.

Castle Hill lies on a promontory overlooking the river Ribble. It has all the hallmarks of a sacred place and an important military position. There was a castle recorded there in the Doomsday Book and the area has been well documented as there had been a priory nearby from the 13th to the 17th century. There is also a motte still present which underwent a partial excavation in the 19th century and is believed to be dated back to either the 7th or 11th century. St Mary’s church now occupies a position at the highest point of the hill. The church dates back to the 11th century and is highly likely to have been built on the site of an existing sacred site. The church has undergone recent excavation works as part of the replacement of the flooring in the nave.

The promontory is the highest point of a ridge which rises gradually from Middleforth to the south. The track along the ridge may have been a processional route in pre-Christian times and St Mary’s Well would probably have been located along such a route. The well was used by the people of Middleforth up to the end of the 19th century, despite the village being located nearly a mile from the well, as it reputedly contained the purest water in the area.

The main road between Liverpool and Preston, now the A59, cuts its way east-west across the ridge, thus separating St Mary’s Well from Castle Hill, with the well lying to the south of the main road. The road runs directly past the well and suggests that the earlier track which the road replaced was used by people from the west of Penwortham and the village of Howick to access the clean water from the spring that fed the well. The older track then veered northwards up the hill and past the church, then ran down to the ford crossing to Ashton. Parts of the original track around the church still exist. It is possible that the Castle was built at that position in order to protect and control the ford.

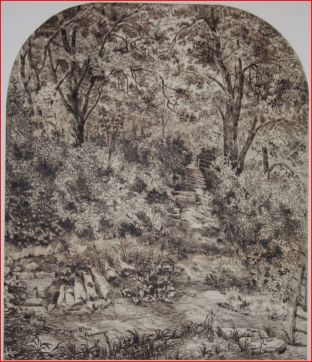

A series of steps cut into the banking at the south of the A59 took people from the track down to the well. The poet Flockhart wrote this in 1854, “On the road which leads from Penwortham Bridge to the Church, at some distance before reaching the avenue leading to the entrance, there is a narrow pathway by which the traveller, after descending a few rude steps, may reach the fields on the left hand. At the bottom of the steps, a little to the right, is a spring of clear water flowing into a sort of natural basin, surrounded by brushwood, near which I have seen primroses and other wild flowers blooming in the greatest luxuriance. This well, like others in the olden time, had its patron saint. It was one of those acts of piety practised by our forefathers to acknowledge the inestimable value of water by dedicating all springs to some saint, but more particularly to the Virgin Mother of our Saviour, as being emblematical of purity. The well at Penwortham, in accordance with this custom, is said to have been dedicated to ” Our Blessed Ladye,” and to have been formerly remarkable for working extraordinary cures; and it is even believed by some to possess this power at the present day; in fact, I have heard many people in the neighbourhood say, that to wash the hands in its water is a certain antidote to evil.”

Local journalist Hewitson reports in the second half of the 19th century that local people regarded the well’s waters as special, possessing magical and remedial properties. This may, in part, have led to the demise of the well. At that time the spring arising from the hill discharged into a basin, wide enough for people to bathe in. However, disease transmission via water wasn’t a known phenomenon until the second half of the 19th century. Up to then the widely held belief was transmission via miasma, or foul air. This belief was seriously challenged after an outbreak of cholera in the Soho district of London in 1854, which was traced to a water pump that had been installed in Broad Street. Overfull and leaking cess pits under the houses had contaminated the supply to the Broad Street pump and had killed 500 people within 10 days of the outbreak. John Snow investigated the outbreak and showed a pattern of infection related to usage of the pump. This was a seminal event in the fields of epidemiology and environmental health and one which was to have almost immediate repercussions 200 miles further north.

Once the link between water and disease had become established, concerns were raised about the suitability of people bathing in St Mary’s Well. Interestingly, it wasn’t the people of Penwortham who would be considered likely to contaminate the well’s water by bathing, but “Irish” people, who happened to be migrating in large numbers around this time. In response to the hygiene concerns the well was effectively capped, the quarried stone basin covered over with stone slabs and a flagstone erected in front, with a pipe outlet through the flagstone being the only access to the waters. The well supplied nearly 6,000 gallons per day to a Penwortham population numbering around 1,400 souls, the flow being sufficient to fill a one and a half gallon pail in 40 seconds.

Towards the end of the 19th century towns were responding to the need for clean water supplies by providing piped water services to residents. This may have provided additional pressure for closing local wells, the economics being such that the town council or water authority needed to ensure as many people as possible subscribed to their service. Preston made attempts to persuade the people of Middleforth and Penwortham to sign up to their piped supply. Some local residents responded by proposing a scheme to run a pipe from St Mary’s Well to Middleforth, to serve around 100 homes.

So important was the well to the Middleforth residents that, when the West Lancashire Railway company decided to build a train line through Penwortham, the residents insisted that a culvert be created in the railway to allow them to walk to St Mary’s Well. The company agreed and the line was opened in 1877.

Though hygiene, economics and convenience would have inevitably played a part in the well’s demise as a regular water source, it was a different factor that brought about the end of centuries of usage within the space of just a few years. On 11th October 1884 the first sod was cut in the construction of Preston Dock. This entailed shifting the course of the Ribble several hundred yards southward, away from Ashton and towards Castle Hill, thus allowing a dock to be created at the original river course at Ashton, now Riversway Docklands.

Work on the docks took place until 1888, by which time the flow from St Mary’s Well had diminished to such an extent that it could no longer meet demand, despite having had remedial works carried out in 1887 to improve the situation. A detailed engineering survey was carried out in 1888 by Mr J Myers, who identified the docks construction as the source of this water flow reduction, the removal of the red sandstone substrate at the river channel breaching the aquifer or basin which fed St Mary’s and other wells. Indeed, during the construction, a new spring appeared at the north of Castle Hill, immediately producing half the flow of St Mary’s Well. The Rural Sanitary Committee had little option but to accept Mr Myers’ recommendation to close the well.

At the time of the 1839 tithe map, Well Field was owned by Richard Aspinwall, the third largest landholder in Penwortham at the time. It was leased out to John Dawson, along with a farmstead and several other fields. Well Field terminated at the site of St Mary’s Well, the well being in the northwest corner of the field. Another field adjoined Well Field at the location of the well, the tithe naming it onomatopaeically as Swash field. “Swash” is a term associated with tidal flows. Anyone who knows this field will recognise its watery aspect, with marsh plants growing in the permanently boggy ground. Despite the field enjoying full sunshine the tithe surveyor rated it well below the value of the adjacent fields, suggesting that it wasn’t suitable for farming back then. Whether the spring water flow from the hill finds its final resting place in Swash field is unknown. One 1844 map suggests that there was a brook which led from a channel of the Ribble to the well, though this might have been an error by the map’s colourist. The site of St Mary’s Well continued to appear on maps up to the early 20th century.

In 1961-2 the carriageway of the A59 along Penwortham Brow was widened. This entailed some earthworks to the banking to the south of the roadway and recutting the steps down to the well. St Mary’s Well now lies somewhere beneath the southern embankment of the A59. There have been reports of local residents saying that they remember the well. It is possible that they do remember St Mary’s Well before the A59 widening of 50 years ago, or possibly they were mistakenly seeing Brotherton’s well, which lay just 7 yards south of St Mary’s Well. In theory Brotherton’s Well could still have been visible after the A59 widening.

However, during construction of the Marsh Lane flyover crossing of the Ribble in the 1980s the fields at the bottom of the steps were used as the vehicle marshalling area for the installation of the bridge sections. After completion of the works the flyover banking and the construction site were made into plantations. The plantation at the bottom of the steps is over 1m higher than the surrounding fields, due to the depth of hardcore required to prevent the contractor’s vehicles from sinking into the sodden earth and the addition of topsoil for the plantation. Despite all this, local people still suggest that springs appear at times near the area of the well and I have witnessed Swash field with standing water even in times of low rainfall.

It is interesting to ponder what we have lost with the demise of St Mary’s Well. A source of pure water, filtered by months or years passing through the soil and strata; a sacred place with magical and healing powers; a social space where residents met regularly whilst collecting their daily water supplies; a link in the chain of understanding that everything we have comes from the Earth; a connection to our ancestors’ lives?

I am grateful for the assistance of Lindsey McCormick, Fine Art Curator at Preston’s Harris Museum and Art Gallery, for finding the Edwin Beattie drawings and granting permission to use them in this article.

The old path to the Well photo courtesy of Lorna Smithers.